Pathways to Justice:

For Women Experiencing Gendered Violence

January 2017 - April 2021

In partnership with the Nova Scotia Association of Black Social Workers

Funded by: Women and Gender Equality Canada

Be the Peace Institute (BTPI) and Nova Scotia Association of Black Social Workers (ABSW) are working together to explore how women who have experienced gendered violence* define ‘justice’, and how to use restorative and trauma-informed lenses, gender-based intersectional analysis, and women’s leadership to identify and implement pathways to achieving that justice.

Interpersonal violence does not only involve the binary of women as victims and men as perpetrators. Anyone can be a victim of violence, including men, those in same sex relationships and those who identify across a continuum of gender identity. However, since evidence supports that the vast majority of situations involve men’s violence against women, this is the focus of the project.

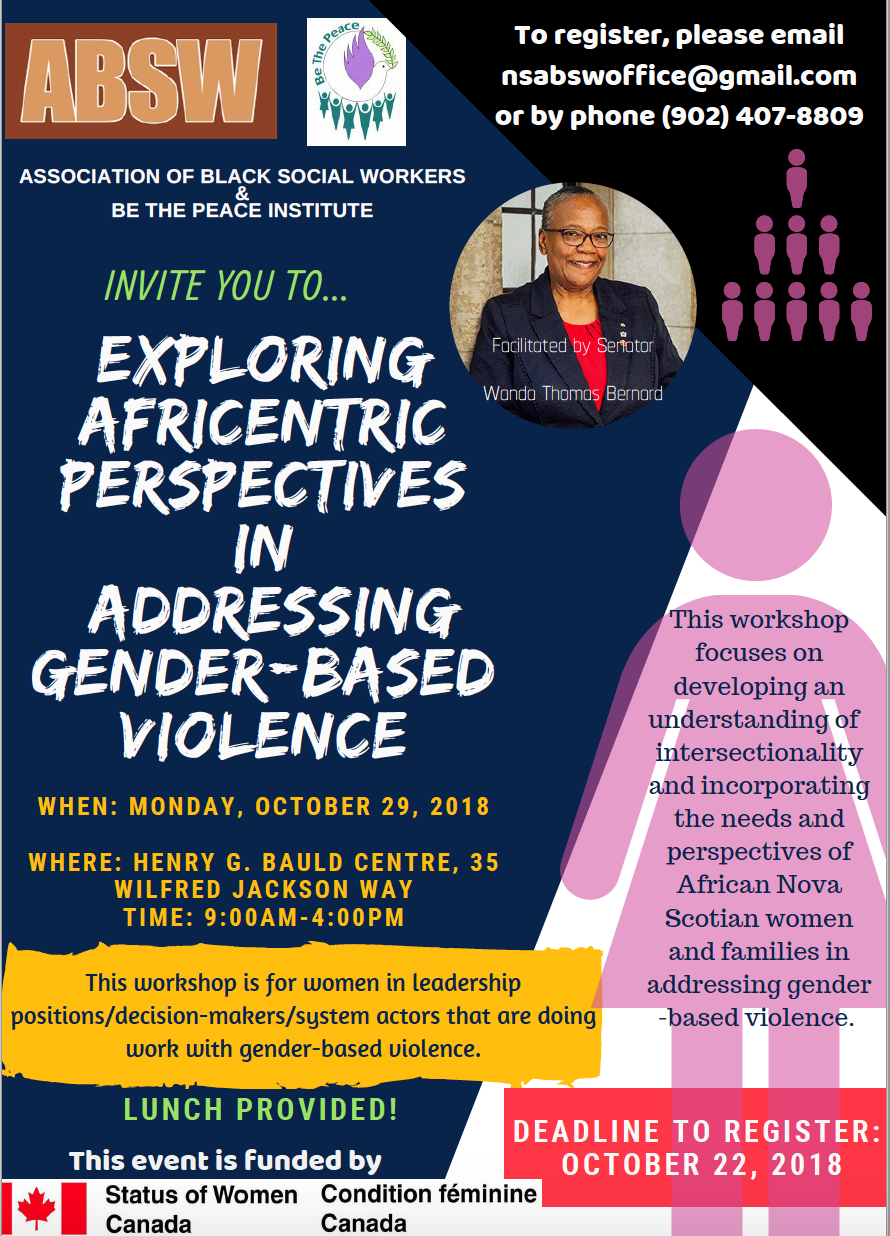

Courtney Brown, Senator Wanda Thomas Bernard, Sue Bookchin, Stacey Godsoe and Danielle Hodges at the “Leading the Way: Africentric Theory and Women’s Leadership”, November, 2017 (the first of four women’s leadership training sessions for this project).

THE AIM

As we keep the voices and direct experiences of women experiencing gendered violence as central to the project, we are asking the questions: What does justice look like from their perspective? Can the criminal justice system deliver unbiased justice? If so, what alterations are needed for that to happen? And if not, then what are the pathways to that justice, who will steward it and how can it be structured and resourced?

It is our assumption that unbiased justice in gendered violence necessarily involves:

Gender intersectional analysis based on understanding the roots of sexism and how patriarchal structures and socially constructed gender norms routinely and profoundly disadvantage and marginalize women in their rights and freedoms, and how this intersects with other forms of oppression such as racism, colonialism, homophobia, ableism, etc.

Trauma-informed approach as a key dimension and competence in understanding the complexities of gendered violence and the neurobiological, emotional and behavioral impacts of trauma on victimized persons, both individually and collectively.

Restorative response at whatever juncture a woman presents for help, support and justice, that honours dignity, respect, compassion for the person who is the target of harm, and a quest for meaningful accountability and repair of those harms.

Inclusion of a diverse range of stakeholders in a highly collaborative effort to make sense of and implement change in the systems involved. These would include: survivors, community-based service providers, women-serving agencies, men’s intervention services, government agencies across sectors (justice, community services, health, education), justice professionals, academics, stakeholders of all genders, racial and cultural identities and social positions.

* We are using “gendered violence” or GV as a term inclusive of domestic, intimate partner, or sexualized violence, and most often, although not exclusively, committed by men against women and girls.

THE ISSUE/NEED: GENDERED VIOLENCE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

Gendered violence crimes are among the most under reported crimes in Canada. And Nova Scotia has had some of the lowest rates of charges, prosecutions and convictions of gendered violence crimes, particularly sexual assault.

High profile media cases and women’s stories have raised awareness that our current criminal justice system fails women who report gendered violence in some significant ways. In spite of mechanisms instituted to protect women, (Rape Shield Laws and Pro-arrest, Pro-charge, Pro-prosecution policies, ODARA risk assessments), these are applied or interpreted inconsistently, leaving some victimized women vulnerable and stripped of agency, dignity and choice.

Gender biases, stereotypes and rape mythologies continue to permeate the discourse inside courtrooms and in the public domain. These, along with the inherently adversarial and incident-based nature of justice processes pose significant barriers for women. For LBTQI+, Indigenous and African Nova Scotian individuals, immigrants, youth, elders, or those with low literacy/education, poverty or disabilities, the risks of both gender-based violence and also of maltreatment by the system rises significantly.

The justice system has been described as a blunt instrument, without nuance, and lacking facility to entertain or address the complexities of relational dynamics and patterns, many of which occur in the private sphere without witnesses and may fail to meet the threshold of ‘beyond a reasonable doubt.’

Women survivors of gendered violence often report feeling blamed, shamed, dismissed, disbelieved, humiliated and re-traumatized by the justice system when they report gendered violence. In the absence of legal counsel and adequate navigation support, they feel unprepared and shocked by their treatment in the system, as if they themselves are on trial. They report little relief from threat and danger by the accused, limited access to vehicles for restoration or therapeutic resources for healing, and caught in the cracks between criminal court and family court proceedings. Justice system professionals and women’s services advocates likewise express frustration at their inability to ensure sensitive treatment to traumatized women and/or just and unbiased outcomes. Current legal mechanisms are insufficient to keep women/families safe from the threat of increasing violence, and a lack of meaningful accountability by offenders is common.

A note on inclusion of women and men: The traditional absence of men and boys in the discourse of preventing and addressing violence against women aligns with relegating gendered violence to the realm of “women’s issues.” This tends to not only exclude, but also alienate and lay blame on a significant number of male-identified people who can intervene and influence male peers when they witness misogynistic or abusive behaviour. The gender binary of women as victims who need to be helped, and men as perpetrators who need to be punished, is not only inaccurate, but unhelpful in understanding the complexities and nuances of gender dynamics, power and privilege, social acculturation, learned behaviour and the multiple and varied impacts and consequences of trauma. By being inclusive of people of all genders we can open possibilities for modelling equality. If we can speak openly together, foster skills in communication and mutual understanding, then we can take action on the common ground of how gender-based violence and confined gender boxes and stereotypes harm us all.

THE OBJECTIVES

The objectives of the project are three-fold, integrated under an umbrella of systemic change in service to justice for women experiencing gendered violence and by extension, their children, families and broader communities.

1) ALTERATIONS TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE PRACTICES THAT CAN PREVENT AND MITIGATE SYSTEM-INDUCED TRAUMA

During the course of the project, in concert with knowledgeable partners, stakeholders and credible evidence, we will identify leverage points in the criminal justice system that hold promise for more humane and dignified treatment of survivors and more just and unbiased outcomes. These may range from: trauma training for police, lawyers and judges; availing survivors of dedicated legal counsel and navigation support; building stronger connections between different courts; encouraging creation of specialized courts that elevate the needs of the victim to equal status with that of the offender; to increasing collaboration among and between sector providers and community-based supports; improved mechanisms for ensuring safety and mitigating threat; achieving meaningful accountability; and enhanced availability of specialized therapeutic services not only for trauma recovery, but also for offenders to alter their use of violence, as this may result in healing for all.

Courtney Brown, Stacey Godsoe and Sue Bookchin presenting project findings at the 6th Canadian Domestic Violence Conference, March 2020.

Screening our documentary at the 6th Canadian Domestic Violence Conference, March 2020

2) USE OF A RESTORATIVE LENS TO INFORM, ENHANCE OR CREATE ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO JUSTICE

With a provincial moratorium in place on the use of restorative practices by justice system actors in gendered violence situations, it is essential to make distinctions between the terms restorative justice, restorative practices, and a restorative approach or response. In Nova Scotia the term ‘restorative justice’ (RJ) commonly refers to a specific format used by Community Justice Societies and their volunteers in the Youth Restorative Justice Program, just recently expanded to include adults. While this model is highly regarded as a leader in the field of RJ, it is insufficiently expert in the complex understandings of gender violence dynamics, trauma and gender intersectional analyses to be applied whole scale to gendered violence. In addition the term is still widely misunderstood in public perception as being soft on offenders, when it may be precisely the opposite.

More recently, some feminist scholars are suggesting the inadequacies of the criminal justice system are an impetus for exploring how a restorative approach can more skillfully achieve the type of processes and outcomes survivors seek. As well, non-government entities, including academics, Indigenous organizations and community-based service providers have been researching, developing and using a restorative approach in various ways to address harms, accountability and the risks inherent in gendered violence situations.

While significant and replicable evaluation data is scarce, there are promising examples of how use of a restorative approach and restorative practices can be effective for all parties. Examples include use by Mi’kmaq Legal Support Network; Bridges Institute and New Start interventions with offenders and family members; Dalhousie University Dental School engagement; and the inquiry into the Nova Scotia Home for Coloured Children.

Hence, the project offers the term ‘restorative response’. With roots in Relational Theory, the approach recognizes the primacy of relationships in human communities in how we navigate, understand, and make meaning of our world. In the context of this project every relational interaction is an opportunity for connection, compassion, humanity, dignity and respect, even in the highly structured confines of the criminal justice system, but also in the creation of new, innovative and more collaborative pathways to justice.

In this context, processes may look entirely different than both criminal justice and traditional restorative justice (while drawing on best practices from both), with much greater attention and expertise devoted to safety, choice, establishing readiness and authentic eagerness to repair harms through individual therapeutic work. It may mean two parties and their supporting communities never convene together unless there is a mutually clear and compelling reason to do so and always on a voluntary basis. In the considerable number of situations where survivor and offender choose to remain in relationship for valid and credible reasons, including, but not limited to co-parenting, a restorative approach is particularly compelling. It may offer: a mutual understanding of the harm caused not only to a survivor, but also to children, family members, and community; meaningful accountability and authentic repair of harm by an offender; and therapeutic services, both for a survivor to heal and rebuild AND for an offender to change abusive behaviour, resulting in the possibility of genuine healing, capacity building, and prevention of further violence.

3) EMPOWERING WOMEN AND AMPLIFYING WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP FOR SYSTEMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGE

While the project welcomes and requires perspectives from people of all genders, it will particularly amplify the individual and collective voices, perspectives and leadership of women for systemic and social change. Voice and agency are powerful tools for social change that, for women, are often underdeveloped, denied, dismissed, disregarded, even ridiculed. This has profoundly diminished women’s critical contributions to changing the structures and systems that tend to marginalize them. Gender inequities persist in all realms and the “feminine” aspects of leadership that tend toward authentic collaboration, connection and finding common ground, remain devalued as “soft skills,” even as they are the very competencies desperately needed in chaotic and complex times. Leadership development may include:

Building widespread capacity in navigating social, political and gender-biased structures at both a personal and systemic scale

Understanding complex adaptive systems and social innovation when dealing with intractable issues and polarities in viewpoints

Building strategic alliances and influence across silos

Gender and intersectional analysis

Effective collaboration

Alternative conflict resolution and decision-making methodologies

Advocacy

Hosting and facilitating meaningful discourse

Skills in articulating clearly and directly the impacts of inequality in one’s life and work, in mixed gender environments to minimize backlash, disregard, and defensiveness.

By enhancing and mobilizing the leadership capacities of women working in justice, government, community, women’s advocacy and academia, in concert with survivors and other stakeholders in diverse communities, we will identify and compel needed changes in justice system structures, policies and practices to achieve real, unbiased justice both within the criminal justice system and also via alternate and innovative means. The aim will be to act as soon as the people, resources, foundations and leadership align for wise action, and with ongoing feedback loops and evaluation frameworks.